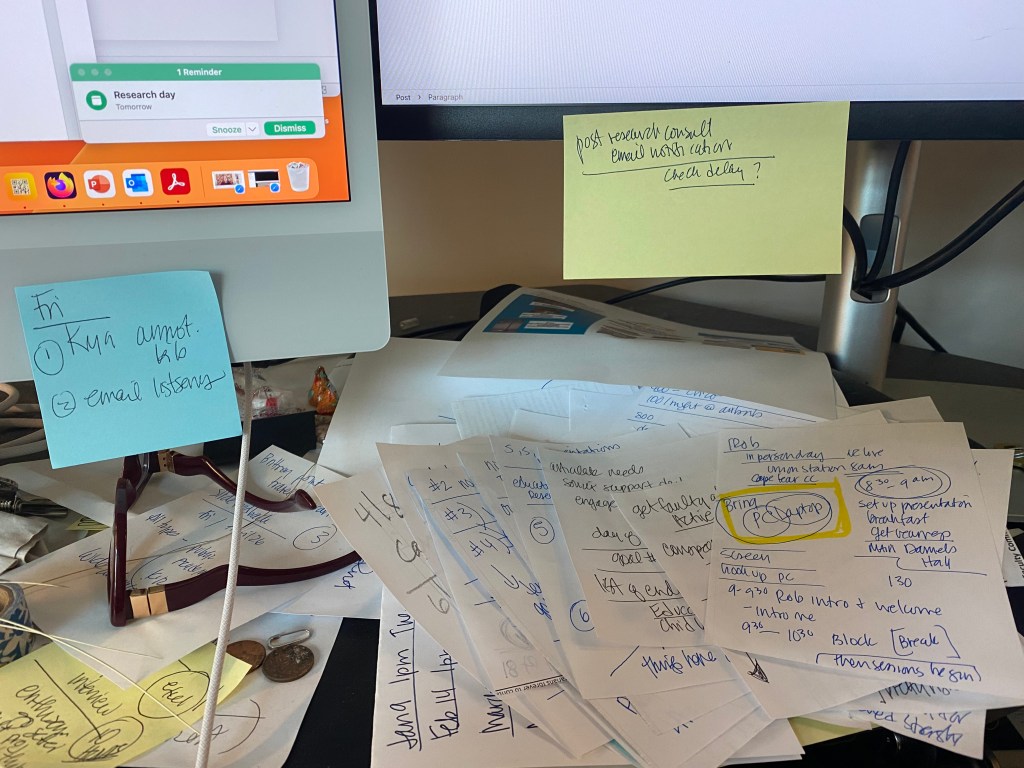

Here’s a look at my desk, littered with scrap paper on which I jotted notes (thanks to my ADHD brain). Didn’t note the source of the article I read that spurred the following thoughts on sustainability and swag.

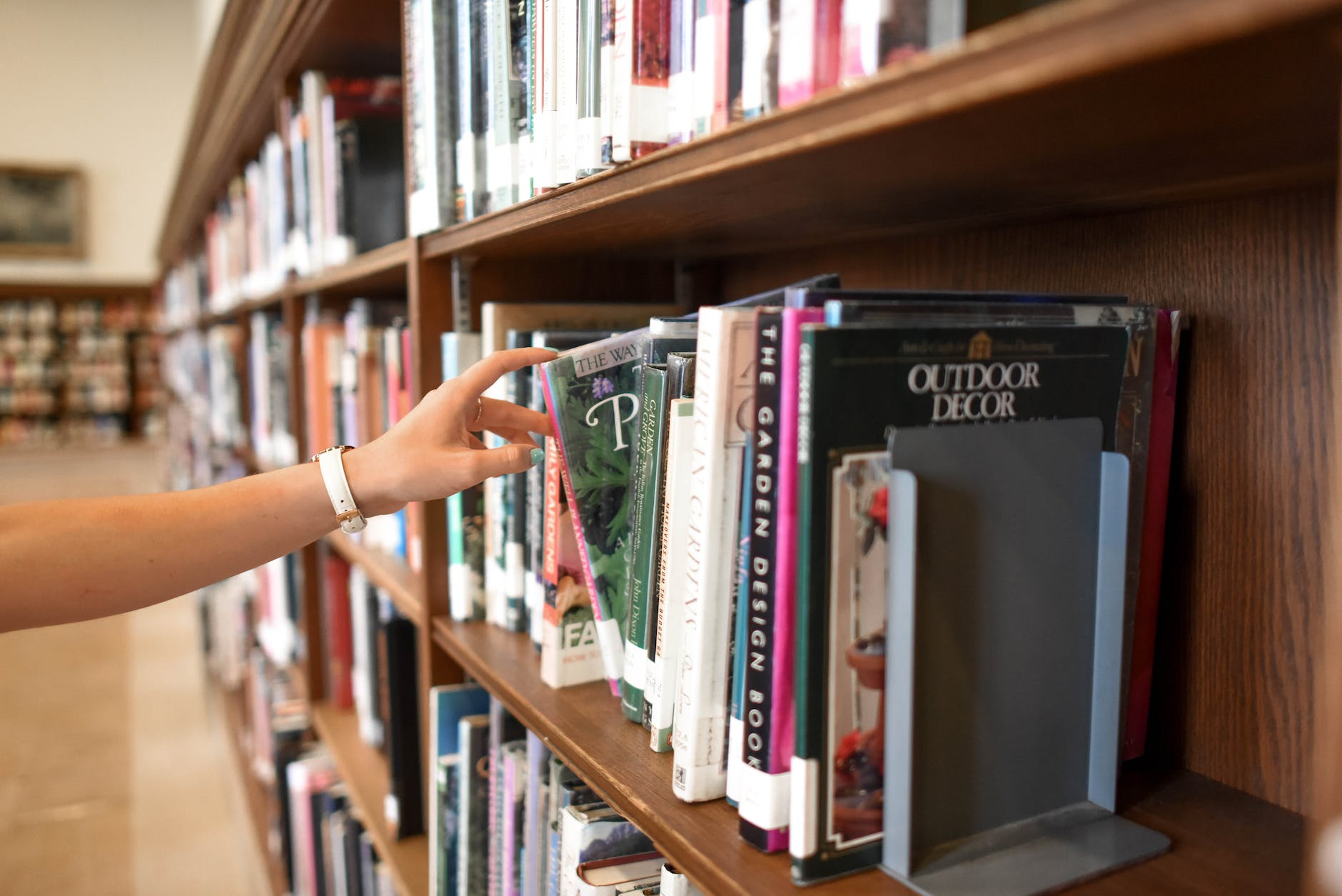

First, about these scraps: Library workers, at least in my experience, were always concerned with sustainability. At 13, as a volunteer library worker, I was asked to chop paper into slips with the paper cutter, so that service desks could write call numbers for patrons1 or patrons could jot those down themselves.

That said, somewhere, recently I read a critique of swag and how that industry creates cheap, mass produced, sometimes single-use-plastic objects that people toss in the trash.

Why give another person crap? Anyone versed in critical thinking may arrive at similar conclusions about this issue. It likely drives the DIY/handmade gifts groundswell.

But better yet, how does this relate to trauma-informed or trauma-responsive libraries?

Safety: do libraries want to encourage people to use plastic, when there’s clear evidence that plastic is killing us and our world? Why add to this problem?

Can libraries explore alternatives to plastic library cards or ID cards? A saving grace is that they are used multiple times. I remember when library cards were paper stock with a metal piece that circ workers stuck in a machine that franked the card # onto the book’s card. I won’t explain the details of that workflow process; it’s a bit hazy in my brain and I don’t want to share incorrect information, though I remember being a cog in that system decades ago.

Trust/transparency: should our patrons trust us when the swag we give them is directly and indirectly affecting their health? Gifting mass-produced, plastic swag to our communities seems like a thoughtless practice in which we jump on the bandwagon of providing prizes and favors for a generation who received them at every birthday party they attend? I’d rather give each kid a $10; in the end it is cheaper.

As a library worker, how do I feel when my efforts and contributions are rewarded with cheap trinkets (aka symbolic intervention)? Gone are the days when companies gave cash bonuses, gifts of quality, or fancy, multi-jewel-operated watches? Lapel pins seem gendered or role-bound and most likely worn by people sporting suits. Front-line workers rarely wear suits.

Do library workers trust companies when efforts at rewarding us fall short?

There’s trend of organizations using swag to recognize employees and increase morale. For the most part, the google results reflect content created by the swag industry propping up these practices and pushing organizations toward solving all their symbolic intervention problems via spending and consumerism.

Also, if our guiding documents, like mission, vision, and goals specifically cite sustainability, and we give out plastic swag, that creates a cognitive dissonance, that the library talks the talk, but doesn’t walk the walk… so if they’re being duplicitous or untruthful about one thing, can we trust them, ever?

Speaking for myself, I prefer a personal note, and a HBR article supports my choice of “symbolic interventions”:

“To make sure your symbolic interventions are well-received, it is important to pay attention to the details. For example, in our studies, the letters of appreciation were signed in ink by a direct manager and mailed to employees’ homes. A blanket email would no doubt have been much less effective.”2

Also, how far can we trust an organization lacking long-term thinking? Plastic is a short-term convenience. I know, I’m probably sounding “shrill.”

Empowerment, voice, & choice: let me choose my own gift. Don’t force something meaningless on me. This reminds me of when servers at restaurants “help” me by placing a straw in my glass. They assume everyone needs a straw. I get you’re being hospitable, but it’s my choice to use a straw or not. Yes, there are many disabled people who require straws, and I’m happy they have them to assist their consumption.

Cultural issues: Environmental racism. All the trash-bound swag ends up in landfills situated in areas mostly adjacent to where BIPOC people live. Or poor people, who are typically BIPOC. In my city, the landfill site is on the southeast side of town, which is poor.

Mostly, I just think that giving people crap is thoughtless and meaningless.

It is performative, lacks integrity and authenticity.

It seems that some libraries are interested in being intentional, like with planning and assessment, policies and procedures. Shouldn’t libraries go the extra mile to be intentional about swag? Have a statement like:

Our library intentionally reduces our impact on the environment by not giving students swag: plastic bags, wrappers, & packaging, single-use pens, and other trash-generating items.

Sure, it could be economically-driven. With rising inflation costs and diminishing library budgets, why waste money on things people throw in the trash?

And look, here’s a sustainable swag self-evaluation for library workers.

But, there’s also a cost to buying “environmentally friendly” items. Like one beverage container to rule them all.

I love tote bags, but I own twenty or more, and when you consider how dirty manufacturing them is? Ugh. I’m part of the problem. According to a 2018 study, I’d have to use my ONE organic cotton toes bag 20,000 times to “offset its overall impact of production.”3

It seems like we’re damned if we do, and damned if we don’t. With that in mind, feeling powerless is inevitable.

However, it’s not up to one person to make a difference. This is a lie we’re taught. Collective action is necessary for changes addressing systemic issues like environmental racism.

- I’m most comfy calling people who use libraries, patrons. Users is pejorative. Customers is yucky. However, I don’t like the assumed power differential that patron, like “patron of the arts,” implies… that their funding of libraries entitles them with power over library workers. ↩︎

- https://hbr.org/2021/03/research-a-little-recognition-can-provide-a-big-morale-boost ↩︎

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/24/style/cotton-totes-climate-crisis.html ↩︎