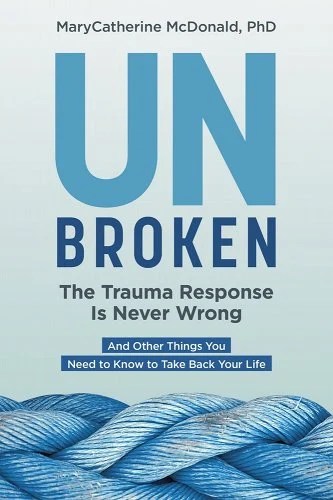

Answering this question will be different for everyone. No two libraries are alike. No two or three libraries employ the same demographics or experience the same organizational behaviors, and so while we can say that “Caring organizations feel safe to library workers,” or “Caring organizations feel welcoming and supportive to library workers,” what that looks like or how it manifests within the organizational dynamic differs greatly.

Given that, what actions can library administration and library leaders take in their creation of a caring organization? Obviously, my first answer is “look to the six principles of trauma informed care.” And yes, those principles guide the majority of my responses.

Safety is critical. I’ve worked with people who shirk in meetings because they expect personal attacks from more senior individuals. When leadership allows bullying, blame shifting, and other negative elements to take root within libraries, library workers don’t feel safe, they experience very limited trust, if any, and they realize that their voices are unimportant. That’s how a culture of silence and complicity permeates some workplaces. And how an organization feels uncaring to its workers.

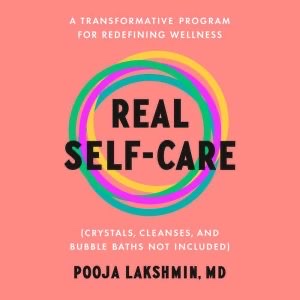

Feeling cared for is relative. We all respond to different means. Having an extra day off is nice. Since COVID my university has granted us one or two paid days leave in addition to the time we accrue and paid holidays. Those were appreciated, but not every library or its parent organization can extend that kind of largesse to workers.

Isabel Espinal suggestions that microaffections and microaffirmations can go a long was in reducing the chilly work environments that POC experiences. Libraries maybe too sterile, too brisk, too “professional.” And as a Latinx person the lack of personal warmth in libraries affects how she feels at work. She recommends that we warm up the library for POC with pleasantries. Pleasantries create connection and caring.

Showing appreciation equitably is another means of spreading care around to everyone working in libraries. It seems as though one of two of the superstars or favorites receive all the accolades from leadership. Library leaderships shouldn’t let opportunities for everyone’s strengths to be acknowledged publicly pass them by.

My library has always been broke, so while there was never an abundance of swag or catered events celebrating library workers, there were times when we felt appreciated. When we were celebrated for no special reason by the dean treating us with a catered sundae bar. Food in workplaces can be tricky (as I wrote a few weeks ago), but, for me, it comes down to intent: Was leadership intentional about demonstrating their care and thoughtfulness for workers? Does leadership care about the impact of their actions? Are library workers invited to the table for the main event, or are they emailed when leftovers are available?